Bitlayer Network: The Computational Layer for Bitcoin

Abstract

Bitcoin's limited transaction throughput and programmability hinder its potential in Decentralized Finance (DeFi). Existing Layer 2 solutions often introduce new trust assumptions, failing to anchor their security directly to Bitcoin's consensus. This paper introduces Bitlayer, a Layer 2 network that solves this challenge using the BitVM paradigm. Our core contribution is a novel, recursive verification protocol that, for the first time, enables a continuous chain of Layer 2 state transitions to be verifiably settled on Bitcoin. This moves beyond mere data inscription to achieve security rooted in Bitcoin's proof-of-work. Furthermore, we deeply integrate BitVM bridge with our rollup protocol to enable secure transfers of Bitcoin assets. Finally, we designed a modular and Turing-complete execution engine, which, powered by a fast consensus mechanism, provides users with sub-second soft finality. Bitlayer unlocks Bitcoin's vast, untapped capital for a new generation of decentralized applications, laying a foundational infrastructure for the Bitcoin DeFi ecosystem.

1. Introduction

Bitcoin [1] holds immense potential for Decentralized Finance (DeFi), but its core design limits transaction throughput and programmability. Activating Bitcoin's vast, untapped capital thus depends on secure and scalable Layer 2 solutions.

However, existing approaches to scaling Bitcoin fall short. Sidechains that rely on federated multisignatures introduce centralized trust, fundamentally undermining Bitcoin's security model. Meanwhile, early rollup designs for Bitcoin can post transaction data to the L1 but lack a mechanism to enforce the validity of state transitions on-chain. This leaves them vulnerable, as their security is not fully guaranteed by Bitcoin's consensus.

This raises a critical question: is it possible to build a Bitcoin L2 that achieves scalable computation while ensuring state validity is enforced by the Bitcoin mainnet itself, without new trust assumptions?

This paper introduces Bitlayer, a Layer 2 network that provides an affirmative answer through rollup architecture [7]. and the BitVM paradigm [2]. overcoming the limitations of both the Bitcoin and existing Layer 2 solutions by enabling scalable computation while anchoring its security to the underlying Bitcoin blockchain. Our primary contributions are as follows:

- A Modular and Turing-Complete Execution Layer: We design and implement a modular execution layer that enables Turing-complete smart contracts, leveraging a meticulously designed blockchain protocol to achieve sub-second soft finality and provide a responsive experience ideal for demanding applications like DeFi and gaming.

- A Recursive Bitcoin Settlement Protocol for Rollups: We design and formalize the first rollup protocol that uses a recursive BitVM-based framework to settle a continuous claim chain of Layer 2 state transitions on Bitcoin. This provides security by anchoring the L2's validity directly to the L1.

- A Synergistic Integration of Bridge and Rollup: We design and implement a secure asset bridge inspired by the BitVM bridge architecture. The core innovation is its deep integration with our rollup protocol, which ensures that asset security and rollup validity are governed by a unified trust model, enabling seamless and secure asset transfers.

2. Network Architecture

Bitlayer operates on a dual-level architecture that combines a Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus for fast block production with a rollup framework that anchors its security to the Bitcoin network. The PoS layer allows validators to sequence transactions and produce blocks rapidly, providing a high-throughput, EVM-compatible environment. The rollup layer then periodically commits and settles the state of this L2 chain onto the Bitcoin blockchain. This design leverages Bitcoin as the ultimate layer for security and data availability, while Bitlayer Network serves as a scalable and efficient computational layer.

2.1. Network Participants and Roles

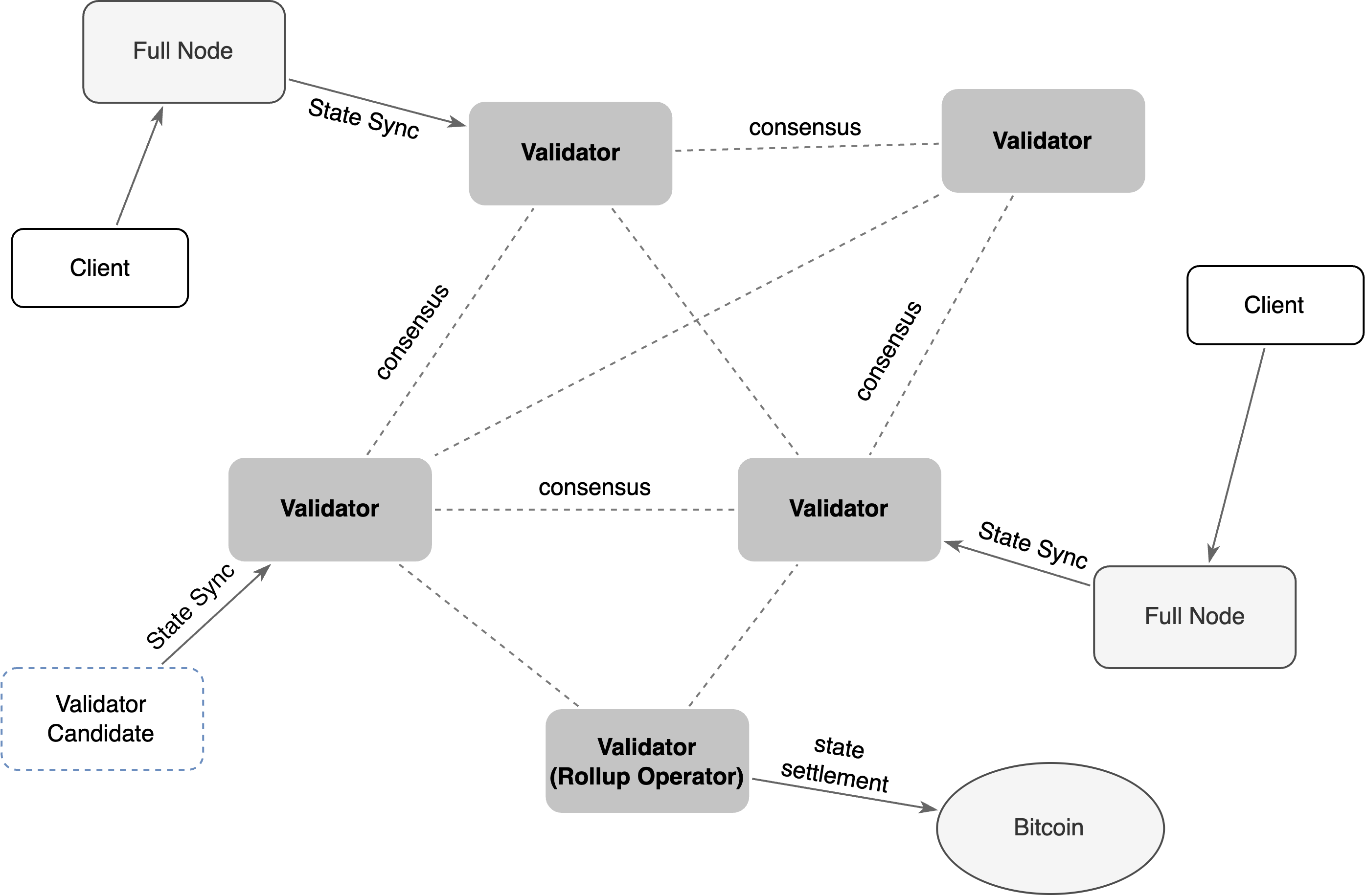

The network is maintained by two key participants: Validators, and Full Nodes.

- Validators: Validators form the backbone of the PoS consensus. They are responsible for producing and validating L2 blocks, ensuring the network's safety and liveness. To join the validator set, a candidate must stake BTR tokens, and their influence in the consensus is proportional to their total stake, which can include tokens delegated by other BTR holders.

- Rollup Operator: The Rollup Operator is a specialized, rotating role assigned to a single validator from the set. This operator is responsible for bundling L2 state transitions into batches, generating cryptographic proofs, and submitting them for settlement on the Bitcoin L1. To ensure accountability and disincentivize fraud, the operator must lock a significant amount of BTC as collateral on L1. The operator role rotates periodically to prevent censorship and centralization.

- Full Nodes: Full nodes maintain a complete copy of the Bitlayer Network blockchain, independently verifying all transactions and state transitions without trusting validators. They play a crucial role in enforcing the protocol rules and ensuring network transparency.

2.2. Dual-Level Transaction Finality

Bitlayer offers a dual-level finality model, giving users and applications a choice between speed and Bitcoin-level security.

- Soft Finality: A transaction achieves soft finality in sub-second once the block containing it is confirmed by Bitlayer's PoS consensus. This provides a fast and responsive user experience, with security backed by the economic stake of the validator set.

- Hard Finality: Hard finality is the highest security guarantee, achieved when the L2 state containing the transaction is settled and finalized on the Bitcoin blockchain. Due to the optimistic rollup's challenge period, this takes approximately seven days. The security for hard finality relies on only a single honest party to challenge fraud, making it nearly equivalent to Bitcoin's own security.

In the rare event of a successful L1 challenge that creates a discrepancy between the L2 state and the settled L1 state, the protocol is designed to halt. The network's recovery would then be guided by social consensus among stakeholders to ensure the integrity of user assets.

3. Settling L2 State on Bitcoin

As a Layer 2 rollup, Bitlayer derives its security from Bitcoin. This chapter details the core mechanism that underpins this relationship: settlement. Settlement is the process by which L2 state transitions, executed in Bitlayer's high-throughput environment, are committed to and finalized on the Bitcoin L1. This allows Bitlayer to inherit Bitcoin's security guarantees. The challenge, however, is achieving this on Bitcoin's constrained, non-Turing-complete script environment.

Our solution is a novel settlement protocol inspired by the BitVM paradigm. This chapter systematically deconstructs this protocol. We first define the concepts of a state claim and explain our hybrid verification approach. After introducing the necessary cryptographic primitives, we detail the protocol for settling a single state claim. Finally, we show how this is extended into a recursive protocol that settles a continuous chain of L2 claims, forming the backbone of the entire rollup.

3.1. Defining the L2 State Claim

At its core, a blockchain is defined by a State Transition Function (STF), denoted as . This deterministic function dictates how the network's State () evolves. A state, which includes all account balances and contract data, is represented by a 32-byte Merkle root. The STF takes the current state and a batch of L2 Transaction Batch () to produce the next state :

where is the index of transaction batch. The entire history of the blockchain unfolds from an initial genesis state ().

A State Claim () is a formal assertion submitted by a Rollup Operator to a smart contract on the Bitcoin L1. Its purpose is to commit to a new L2 state that has resulted from processing a specific transaction batch. This claim acts as the anchor, linking L2 activity to the L1 and enabling Bitlayer Network to inherit Bitcoin's security.

3.2. Cryptographic Primitives

The settlement protocol relies heavily on two advanced cryptographic primitives: Succinct Non-interactive Arguments (SNARGs) and Hash-based One-Time Signature scheme.

3.2.1. Groth16 SNARG

Following the Groth16 paper [4], a SNARG for a relation consists of three probabilistic polynomial-time algorithms (Setup, Prove, Vfy):

- : A setup algorithm that produces a common reference string for a given relation.

- : A prover algorithm that, given the common reference string , a claim , and a witness , generates a proof argument .

- : A verification algorithm that accepts or rejects the proof.

The SNARG satisfies perfect completeness, computational soundness, and what we define as full succinctness.

Definition 3.1 (Full Succinctness): A protocol (Setup, Prove, Vfy) is fully succinct if the verifier Vfy runs in time polynomial in the security parameter , and the size of the proof is also polynomial in .

3.2.2. Hash-based One-Time Signature (HOTS)

The Bitcoin script language, with its OP_CHECKSIG opcode [6], is designed to verify signatures for transactions, not for arbitrary off-chain messages. While proposals like BIP348 exist to extend this functionality, they require a network consensus change. To overcome this limitation, We utilize a Hash-based One-Time Signature scheme (HOTS) [5, 8]. This approach is particularly advantageous as hash functions are native and computationally inexpensive operations within Bitcoin script.

Our variant of HOTS consists of four algorithms:

- : Generates a secret key and public key pair from a security parameter.

s: Publishes a commitment to the Bitcoin script, preparing it to verify a signature for a message of length .w: Signs a message with the secret key to produce a witnessw.- : Verifies the witness

w. If valid, it returns1and reveals the original message on the stack for further on-chain processing.

This final property—the on-chain revelation of the signed message—is a critical component for linking consecutive state claims, as will be detailed in Section 3.5.

3.3. Protocol Overview

The entire settlement protocol is embodied in a BitVM-style smart contract, which is not a single, monolithic contract but rather a complex graph of pre-signed Bitcoin transactions. Participants must jointly pre-sign this transaction graph and are bound to interact strictly according to its predefined pathways. Whereas the original BitVM protocol focused on settling claims about events on both external chain and the Bitcoin for bridging purposes [3], Bitlayer's protocol is more intricate. It must settle a continuous sequence of claims, each representing a discrete change in the L2 state, and guarantee that this sequence is consecutive and unbroken.

The protocol can be conceptualized as a recursive structure. In Section 3.4, we will first elaborate on the sub-protocol for settling a single state claim. Then, in Section 3.5, we will detail how this single-claim verification mechanism is recursively embedded within a broader protocol that settles a continuous chain of claims. By combining these two components, we construct the complete rollup protocol for settling the Bitlayer Network state on Bitcoin.

3.4. Settling a Single Claim

3.4.1. The BitVM2 Paradigm

The on-chain verification of a claim is conducted optimistically. The verifier program in our case is expressed in Bitcoin script. However, as demonstrated by the groundbreaking work of the BitVM Alliance on a Groth16 verifier, a monolithic implementation of such a verifier is far too large to execute directly within a single Bitcoin transaction. Therefore, the BitVM2 paradigm [2] splits the large verifier program into a chain of smaller sub-programs, or "chunks." The protocol then proceeds as a fraud-proof game, where it is assumed the operator's claim is correct unless a challenger can pinpoint an incorrect computation step between two specific chunks.

3.4.2. Protocol Roles

The BitVM smart contract for claim settlement involves a well-defined set of participants:

- Attesting Committee: Rather than forming a new entity, the existing validator set of the Bitlayer Network serves as the attesting committee. This committee is collectively responsible for pre-signing the transaction graph that defines the protocol.

- Protocol Participants: The active participants in the settlement game include a single, designated Operator responsible for submitting claims and any number of Watchers. Watchers can be anyone, including other validators, and their role is to monitor the operator and challenge fraudulent claims.

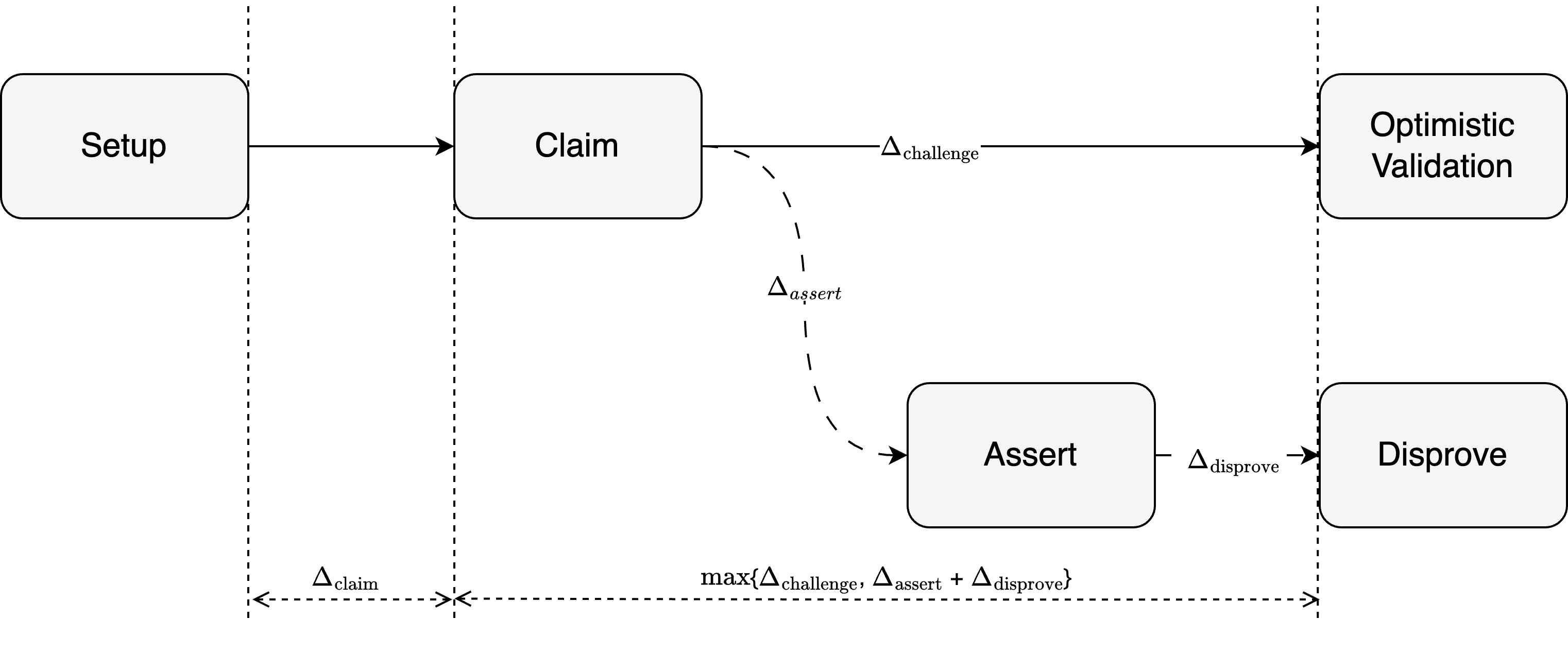

3.4.3. Single Claim Verification Protocol

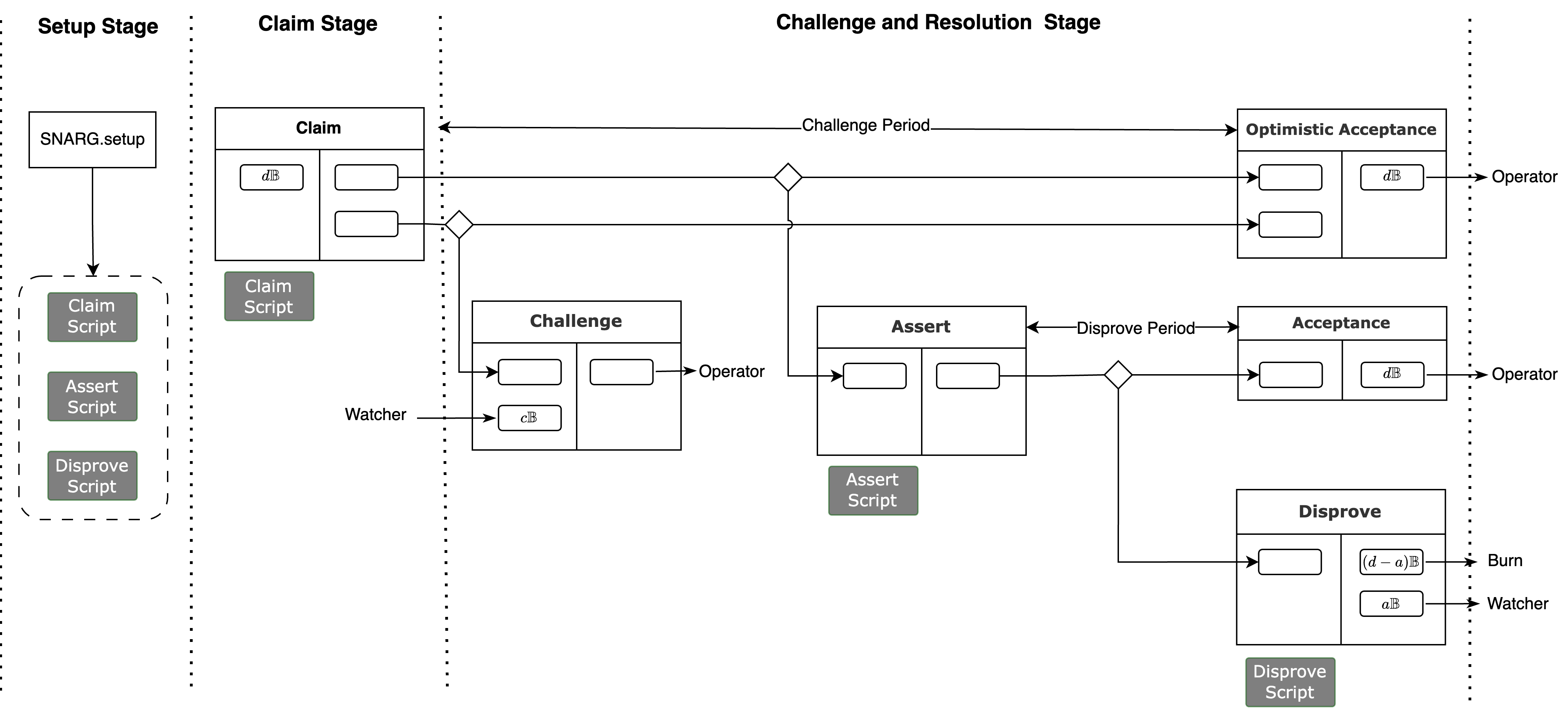

The protocol for verifying a single claim unfolds as a timed challenge-response game governed by Bitcoin time locks. It ensures that both the Operator and any Watcher must act within specified time bounds or face penalties. The protocol can be broken down into three primary stages, which correspond to a series of interconnected Bitcoin transactions pre-signed by the Attesting Committee.

1. Setup Stage

Before the game begins, a trusted public setup generates the necessary scripts. The STF () is used to create a common reference string via SNARG.Setup. The verifier program is split into a set of smaller sub-programs . Three types of locking scripts are created: a Claim Script to initiate the process, an Assert Script for the Operator to post results of all , and a set of Disprove Scripts, one for each sub-program, which Watchers can use to prove fraud. The Claim Script and Assert Script are composed of multiple HOTS, which force operator to post signed claim and results of all sub-programs. The Disprove Scripts include all sub-programs and are organized within a Taproot address. These scripts are then embedded into the outputs of the pre-signed transaction graph.

2. Claim Stage The Operator initiates the process by publishing a Claim transaction, which spends from a previous UTXO and locks their collateral (e.g., BTC). To unlock this input, the Operator must use their HOTS key to sign and reveal the state claim . This action starts a timer, . Watchers observe this claim and can run the STF locally. If they find the claim to be invalid, they can issue a Challenge transaction before the timeout. If no challenge occurs, the Operator reclaims their collateral via an Optimistic Acceptance transaction, and the claim is considered settled.

3. Challenge and Resolution Stage If a Watcher issues a Challenge transaction (which may require them to post a smaller collateral, BTC, to deter frivolous challenges), the pessimistic path is taken. The Operator is now compelled to execute an Assert transaction. In doing so, they must run the chunked verifier program locally and use their HOTS key to sign and publish the results of all sub-programs . This action starts another timer, .

The Watcher now examines the sequence of results published by the Operator. If the Watcher can find a single sub-program where the Operator's published output is inconsistent with the execution of on the Operator's published inputs, they have found fraud. The Watcher can then construct a Disprove transaction. This transaction spends the output corresponding to the fraudulent sub-program, executing that small chunk of logic on-chain to prove the inconsistency. A successful Disprove transaction forfeits the Operator's collateral, a portion of which ( BTC, where ) is awarded to the Watcher. If the Operator correctly publishes results of all , and the Watcher fails to submit a valid Disprove transaction in time, the Operator can finalize the claim via an Acceptance transaction and recover their collateral.

3.4.4. Security Properties

This protocol is designed to be secure under the assumption of at least one honest Watcher. Its security rests on three key properties, which are analyzed in detail in Chapter 6.2.

- Completeness: An honest Operator who correctly follows the protocol and submits valid state claims will never be unjustly penalized.

- Soundness: A dishonest Operator who submits a fraudulent claim cannot avoid being penalized, as an honest Watcher will always be able to construct a valid Disprove transaction.

- Efficiency: The entire claim verification process, whether it results in acceptance or rejection, is guaranteed to terminate within a bounded timeframe defined by the protocol's time locks.

3.5. Settling a Chain of Claims

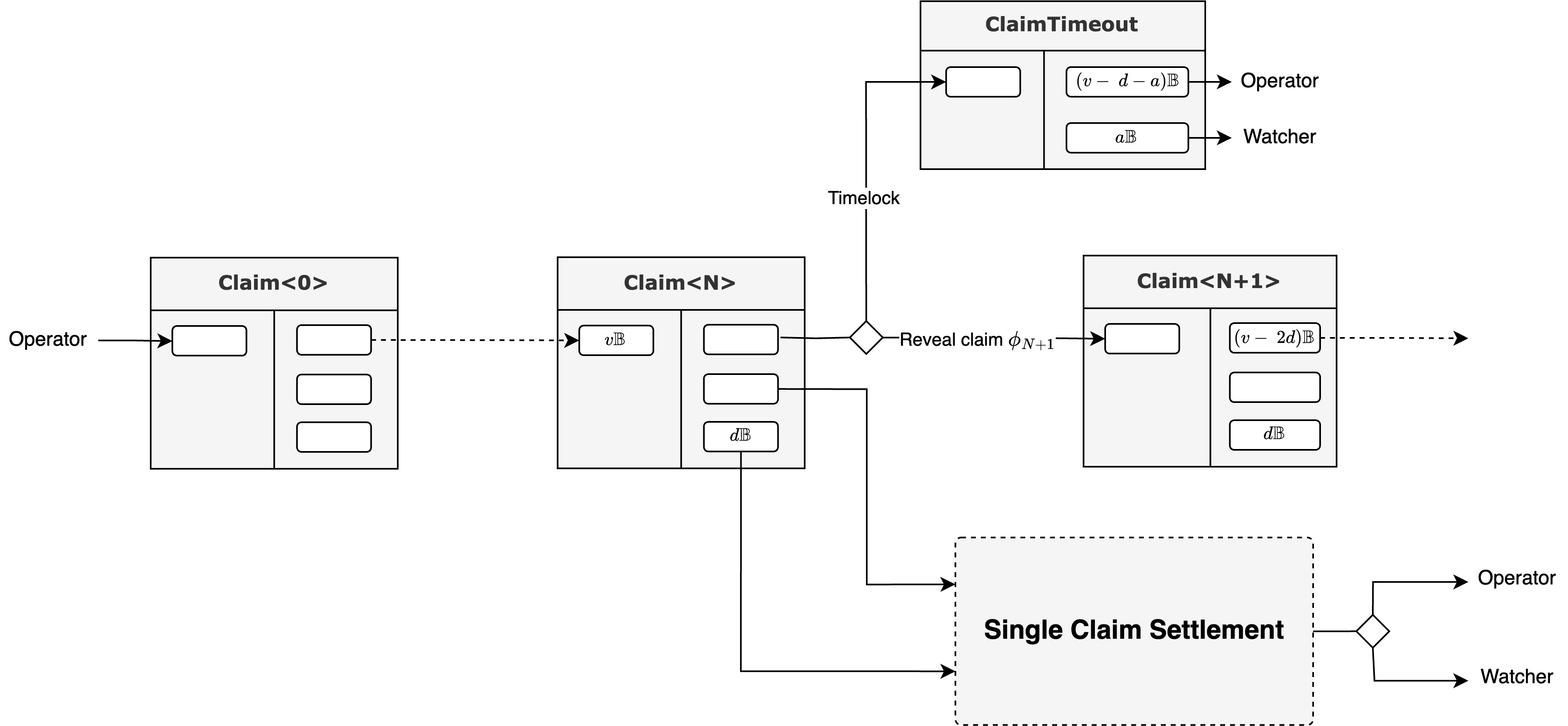

The protocol described above is sufficient for settling a single, isolated claim. However, a rollup requires the continuous settlement of a sequence of claims that represents the ongoing evolution of the L2 state. This is achieved by extending the protocol to recursively chain claims together.

3.5.1. Linking Claims with HOTS

The key to chaining claims lies in the transaction graph's structure. Each Claim transaction, in addition to its other outputs, creates a special UTXO called a claim connector. To submit the next claim (Claim ), the Operator must spend the claim connector UTXO created by the transaction for Claim . The locking script for this connector requires the Operator to use their HOTS key to sign and reveal the data package for Claim . This design naturally links adjacent claims into a chronological and unforgeable chain, as each claim transaction can only be created by consuming an output from its direct predecessor. Bitcoin time locks are used to enforce a regular cadence, preventing the Operator from submitting claims either too quickly or too slowly.

3.5.2. The Trunk Transaction Graph and Parallel Verification

This recursive structure results in a transaction graph with a primary trunk that links the sequence of claims. At each claim on the trunk, a complete sub-graph for single-claim verification (as described in Section 3.4) branches off.

A critical feature of this design is that the submission of the next claim does not need to wait for the final resolution of the previous claim's verification sub-protocol. The Operator can submit Claim while the challenge window for Claim is still open. This parallelism is efficient but requires a mechanism to handle cascading failures. If Claim is successfully challenged, the protocol ensures that its state is invalid, which automatically invalidates the premise of all subsequent claims (). A rational Operator, upon having a claim successfully challenged, is economically incentivized to cease submitting further claims, as each would require posting collateral that is doomed to be forfeited. The trunk would then terminate via a ClaimTimeout transaction.

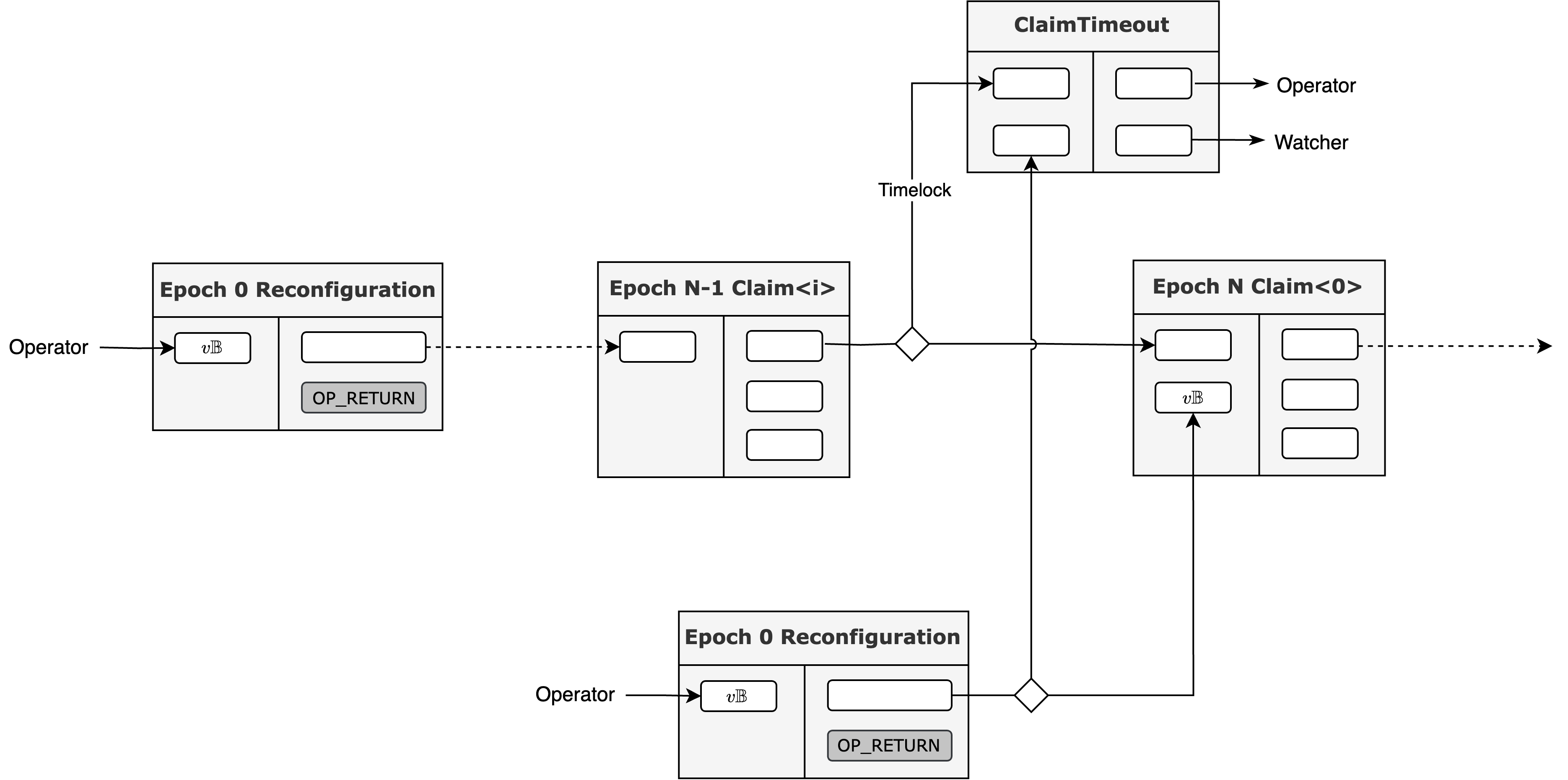

3.5.3. Transaction Graph Reconfiguration and Epochs

Constructing, pre-signing, and storing a transaction graph intended to last for the entire lifecycle of the rollup (e.g., 100 years) is computationally and logistically infeasible for validators. It would also require an impossibly large amount of BTC to be locked as collateral upfront and would preclude any future protocol upgrades.

To solve these problems, we introduce Reconfiguration. The protocol's timeline is divided into discrete epochs, with each epoch consisting of a fixed number of claims (e.g., lasting for two weeks). At the transition between epochs, a reconfiguration event occurs. For each attesting ceremony, the validator set only needs to pre-sign the trunk transaction graph for the upcoming epoch. This makes the burden on validators manageable.

The Exit Window: Reconfiguration is also the point at which protocol upgrades or changes to the validator set can occur. These changes may alter the security assumptions or trust parameters of the system. To protect user sovereignty, Bitlayer provides a mandatory Exit Window. The configuration for Epoch is proposed and finalized during Epoch . This gives users the entirety of Epoch to review the new validator set and transaction graph for Epoch . If a user does not approve of the upcoming changes, they have a full epoch to exit the system by withdrawing their assets (e.g., pegging-out BTC via the BitVM Bridge) before the new configuration takes effect.

Validator Incentives: All validators are required to stake BTR tokens to participate. The pre-signing ceremony for each epoch's transaction graph is coordinated through a system contract on the L2. Failure to participate in the ceremony in a timely manner results in the forfeiture of a portion of the validator's staked BTR, strongly disincentivizing attacks designed to stall the protocol.

3.5.4. The Reconfiguration Process

The reconfiguration process is orchestrated by the L2 system contract. The designated operator prepares all necessary information for the next epoch's transaction graph, and each validator independently generates it, signs it, and submits their signature to the L2 contract. Once a supermajority () of valid signatures are collected, they are aggregated, and the attestation is complete.

This process culminates in a Reconfiguration transaction on Bitcoin. This transaction locks the aggregate collateral required for all claims in the new epoch and records the updated configuration parameters, such as the verifier program commitment , the operator's identity, and time lock values. Reconfiguration transactions must be issued immediately after pre-signing is completed to promptly announce configurations. The very first such transaction, the Epoch 0 Reconfiguration transaction, bootstraps the entire rollup protocol and records the genesis state of the Bitlayer Network.

3.6. Summary

In summary, the Bitlayer settlement protocol materializes as a perpetual, yet manageable, BitVM-style transaction graph on Bitcoin. This graph is cyclic, composed of per-epoch sub-graphs that are linked together through reconfiguration transactions. Each epoch's sub-graph contains a trunk of chronologically linked state claims, and each claim is accompanied by its own verification sub-graph—a sophisticated challenge-response game that allows any single honest participant to enforce the correctness of the L2 state. This architecture enables Bitlayer to achieve a high degree of scalability and programmability while being securely anchored to Bitcoin's unparalleled proof-of-work consensus.

4. State Transition Function and Batch Execution

While Chapter 3 established the protocol for settling a state claim on Bitcoin, this chapter defines the computational process that a claim asserts to be valid: the Bitlayer STF. A correct state transition over a batch of L2 blocks is the fundamental unit of progress for the rollup. Here, we specify the components of our unique, EVM-based STF and present the multi-stage, recursive proving pipeline that generates proofs for its execution. This entire computational process is what an Operator asserts with their claim and what any Watcher can challenge through the settlement game.

4.1. The Bitlayer Network STF

The Bitlayer Network's STF aligns with the battle-tested principles of the Ethereum EVM [9] to provide a familiar and powerful environment for developers. As a Bitcoin rollup, however, it extends the EVM with additional system-level logic and specialized contracts to address its unique requirements, such as handling bridged Bitcoin assets and processing messages from the L1.

4.1.1. Gas and Fees

Transaction fees on the Bitlayer Network are paid exclusively in BTC. This design choice provides a seamless and consistent experience for Bitcoin users, as they can use the asset they already hold without needing to acquire a new, native token for network operations. While transactions are paid for in BTC, the fee rates are extremely low, reflecting the efficiency of the Layer 2 architecture.

Bitlayer implements a multi-dimensional gas model that separates transaction costs into three distinct components:

- Execution Fee: Covers the computational cost of executing the transaction in the EVM, similar to the standard Ethereum model.

- Storage Fee: Accounts for the cost of modifying the L2 state, such as creating new accounts or updating contract storage.

The Execution and Storage Fees are distributed among the validators who secure the network. This fee distribution mechanism creates a precise and sustainable economic model.

4.1.2. Protocol Contracts

Protocol contracts are a set of special-purpose smart contracts that exist at genesis and form an integral part of the Bitlayer protocol. While their logic is central to the network's operation, implementing them as smart contracts rather than native code provides a clear interface and allows for future upgrades through the established governance procedure.

System Config Contract

The System Config contract acts as the network's central control panel, managing core protocol parameters as key-value pairs. Examples include the block gas limit (<block_gas_limit, 10,000,000>) and validator set size.

- Reconfigurability: Most parameters can be updated via governance proposals.

- Update Cadence: The timing of these updates depends on their impact. Some parameters, like certain fee multipliers, can be adjusted at any block boundary. Others that have deeper systemic effects, such as those related to the consensus engine, can only be modified at an epoch boundary to ensure a safe and orderly transition.

- Security: Since many of these parameters are read directly by native protocol code, modifications must be carefully evaluated to ensure they do not compromise network stability or security.

Validator Management Contract This contract governs the lifecycle of the Bitlayer Network's validator set, which is crucial for both L2 block production and L1 attestation ceremonies.

- Validator Admission and Removal:

- To become a validator candidate, a user must stake a minimum amount of BTR tokens in this contract. Candidates are promoted to the active validator set at the beginning of the next epoch. To maintain network stability, the number of new validators promoted from the candidate queue to the active set is capped in each epoch (e.g., at 10% of the total set size).

- Voluntary exits by active validators are similarly subject to a per-epoch cap.

- A validator whose stake falls below the required minimum due to slashing will be forcibly removed from the active set at the next epoch boundary.

- Operator Election:

- For each epoch, the protocol selects one Rollup Operator from the active validator set. The selected Operator is then required to submit a collateral deposit transaction on the Bitcoin L1 within a specified time frame. Failure to do so penalizes the non-compliant validator and triggers a new election to ensure the liveness of the settlement process.

- Rewards and Penalties:

- Validators are rewarded with BTR tokens for securing the network. Rewards are distributed in proportion to each validator's total stake.

- The L2 block proposer receives transaction fee and a larger share of the block reward.

- The designated Rollup Operator receives additional BTR rewards to compensate for the operational costs of settling state claims on Bitcoin L1.

- Validators who participate in the pre-signing ceremony for each epoch's transaction graph receive attestation rewards.

- Failure to adhere to protocol rules (e.g., missing block votes, failing to participate in the pre-signing ceremony) results in penalties, where a portion of the validator's staked BTR is slashed.

Bitcoin Light Client (BLC) Contract The BLC contract serves as the network's trustless gateway to the Bitcoin L1. It has two primary responsibilities: tracking the canonical Bitcoin chain and processing L1-to-L2 messages.

- Canonical Chain Tracking: The protocol relies on oracles to submit Bitcoin block headers to the BLC. By default, the Rollup Operator fulfills this role. However, if the Operator fails to do so, anyone can submit the block header, ensuring liveness. The BLC contract tracks all submitted headers, including those from ephemeral forks, and maintains the canonical chain by following the heaviest-chain rule. A submitted block is then considered finalized after accruing a number of subsequent confirmations defined by a threshold in the System Config Contract (e.g., six).

- L1-to-L2 Message Processing: The BLC contract scans finalized Bitcoin blocks for specific L1-to-L2 messages and translates them into executable L2 transactions called intrinsic transactions. These messages include:

- Bridge Deposit Events: When a user deposits BTC into the BitVM bridge contract on L1, they inscribe a

Bridge Deposit Event. The BLC contract detects this event and generates a correspondingBridge-Mintintrinsic transaction on L2 to credit the user with the equivalent wrapped asset. This automates the peg-in process without requiring a separate user action on L2. - Forced Transactions: A user can force the inclusion of an L2 transaction by inscribing its data directly onto the Bitcoin blockchain. This provides a powerful censorship-resistance mechanism, ensuring that a user can always interact with the rollup even if the entire L2 validator set attempts to censor them.

- Bridge Deposit Events: When a user deposits BTC into the BitVM bridge contract on L1, they inscribe a

The protocol enforces the timely processing of these messages through both its consensus and rollup mechanisms:

- Consensus Enforcement: Before proposing a new block, a validator must query the BLC contract to generate any pending intrinsic transactions. These transactions must be included at the very beginning of the proposed block, ahead of any regular user transactions. If the number of intrinsic transactions exceeds the capacity of a single L2 block, they are processed across multiple blocks in a deterministic order.

- Rollup Enforcement: The STF definition requires that a state claim for a batch of L2 blocks must correctly process all L1-to-L2 messages from the corresponding finalized Bitcoin blocks. Any Operator who submits a claim based on a state that omits or incorrectly processes an L1 message has submitted a fraudulent claim and will be successfully challenged and penalized.

Bridge Contract The Bridge Contract on L2 works in tandem with the BitVM bridge contract on L1 to facilitate the secure, bidirectional flow of assets.

- Peg-In: The contract processes the

Bridge-Mintintrinsic transactions generated by the BLC, minting the corresponding L2 wrapped assets to the user's account. - Peg-Out: To withdraw assets, a user initiates a transaction on L2 that calls the Bridge Contract. The contract burns the user's L2 assets and emits an L2 event. This event serves as a message that is later picked up by the L1 bridge mechanism to process the withdrawal.

- Proof of Reserves (PoR): The contract maintains a complete and transparent ledger of all bridged assets on Bitlayer, enabling anyone to generate a Proof of Reserves at any time.

The detailed architecture of the bridge and the peg-out mechanism will be further explored in Chapter 5.

4.2. Proving Pipeline

To verify the state transitions of this Rollup protocol, the protocol adopts a multi-stage, asynchronous, recursive proving system based on a zero-knowledge virtual machine (zkVM). The system is designed to generate a wrapped proof that is both compact and easy to verify on the Bitcoin network, while ensuring the entire proving system is secure and upgradable through a governed process.

4.2.1. Integrity and Upgradability via CodeControlGroup

The integrity of the entire proving pipeline depends on the ability to ensure the validity and integrity of its core computation engine—that is, all programs running in the zkVM, including the block execution logic, batch aggregation logic, and recursion logic. The CodeControlGroup is the core security mechanism designed for this purpose.

CodeCommitment: The Unique Fingerprint of a zkVM Program

The zkVM generates an unique cryptographic commitment for each complete program suite, known as the CodeCommitment. This commitment serves as a unique and immutable fingerprint for a specific version of the program. Any change to the code, no matter how small, results in a completely different CodeCommitment. This holistic commitment is crucial, as it effectively prevents attack vectors where a fraudulent proof is generated by tampering with some components while others appear unchanged.

CodeControlGroup: An Index-Based Authorization Registry

The CodeControlGroup is a cryptographically enforced authorization list that records all valid CodeCommitments. Its core design is not a flat set, but rather an index-based structure. Throughout the proving pipeline, every program execution occurs within a specific context, which is marked by a unique Index (e.g., a block height). The CodeControlGroup maps each Index to a whitelist of valid CodeCommitments. Its data structure is a Hierarchical Merkle Trees with Merkle Mountain Range (MMR).

This index-based mechanism is critical. It allows the system to precisely determine whether the program used was on the whitelist for that specific Index when verifying any historical proof. This ensures the integrity of all programs throughout the entire recursive chain, precluding the possibility of using unauthorized or outdated program versions to generate historical proofs. The root, the CodeControlRoot, serves as a commitment to the entire authorization history, making the registry itself tamper-evident.

Secure Upgrade Path

The system's upgrade path is structured around discrete Epochs (as described in Section 3.5.3). Changes are introduced via an Epoch Reconfiguration event at each transition. This event defines the new set of system parameters, with the CodeControlGroup being a critical component, and this data is submitted to both Bitcoin and the L2. To simplify pipeline implementation and trust management, the proving pipeline does not scan blocks for this information. Instead, it receives the appropriate CodeControlGroup for a given context as a direct configuration input. The integrity of this entire process is guaranteed by the synchronization between the Epoch transition and the pre-signing mechanism. The new CodeControlGroup is finalized by governance, and its corresponding CodeControlRoot is locked in on-chain via the pre-signing mechanism before the new Epoch becomes active. This ensures that if a prover uses an incorrect CodeControlGroup, the resulting proof will be rejected during on-chain verification, as its CodeControlRoot will not match the pre-signed value for that Epoch. Therefore, the CodeControlGroup provides a transparent and secure governance framework for the evolution of the zkVM's core logic. Its root, the CodeControlRoot, serves as the final commitment to the system's complete authorized history, anchoring the validity of the entire recursive proof chain in a foundation of cryptographic certainty and governance consensus.

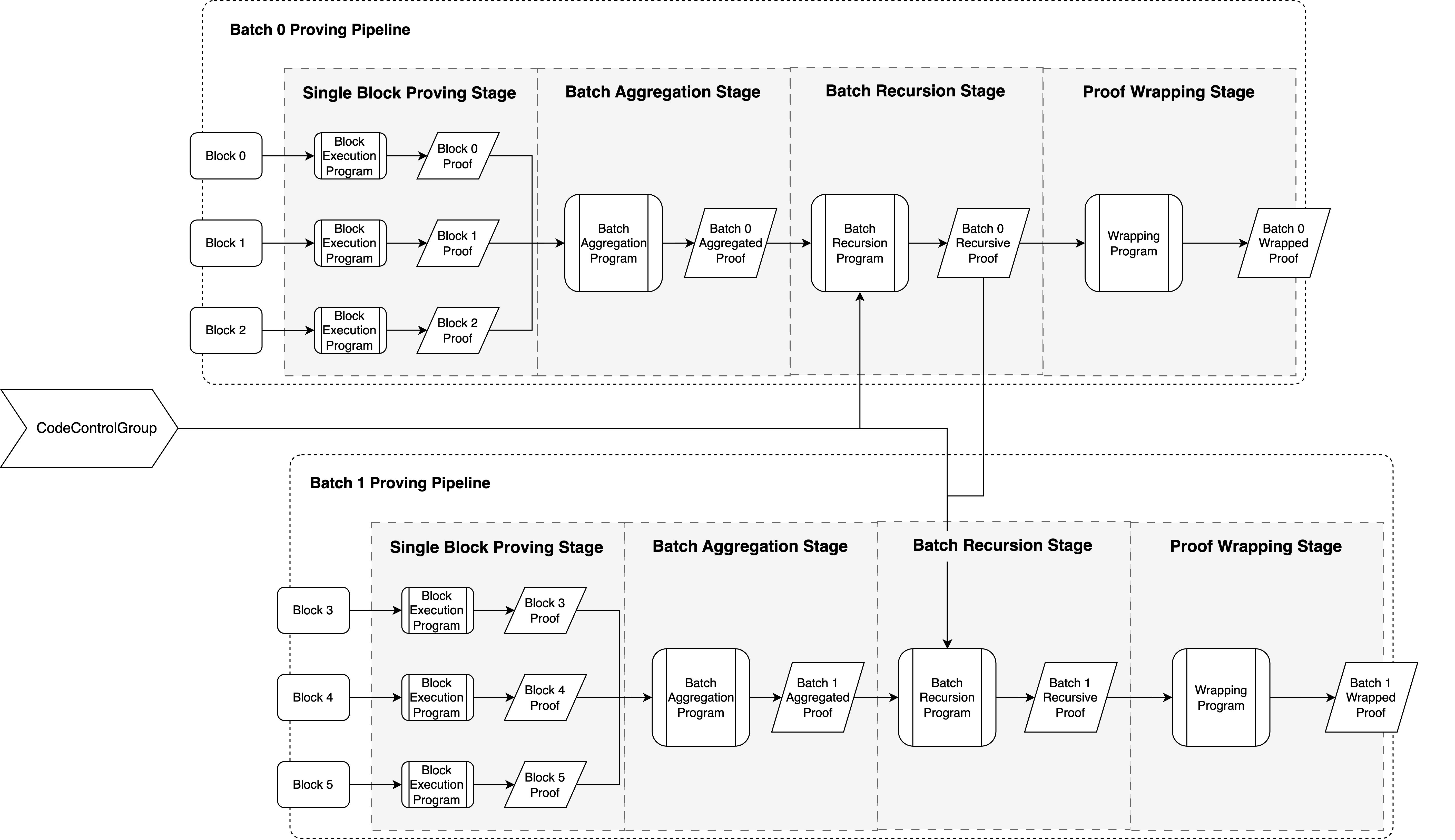

4.2.2. The Four-Stage Recursive Proving Pipeline

Overview

The protocol's proving workflow is a sequential pipeline consisting of four distinct stages. Before delving into the stages, it is important to understand the basic data structures involved. Each Block has a unique Block Number, which serves as the Index for contextual verification within the CodeControlGroup. Blocks are grouped into a Batch for aggregation. The criterion for forming a batch is a key, governable system parameter, which can be either a fixed number of blocks or a specific time duration. Finally, the protocol's timeline is organized into Epochs to manage system-wide reconfigurations.

The four stages of the pipeline are: Single Block Proving, Batch Aggregation, Batch Recursion, and Proof Wrapping. This structure operates as a nested pipeline: within each batch, proofs flow sequentially through the stages, while a higher-level pipeline links consecutive batches together through the recursive stage. Each stage receives specific inputs, performs computations within the zkVM, and generates outputs that either feed into the next stage or contribute to the wrapped proof. This recursive architecture enables the efficient aggregation and compression of proofs, thereby enhancing system scalability. The following diagram illustrates this nested pipeline structure.

Pipeline Design Rationale The multi-stage pipeline design is a deliberate architectural choice made to optimize the trade-offs among proving efficiency, system complexity, and security.

- Parallelization in Stage 1 for Efficiency: Proving the state transition of a single block is the most computationally intensive task in the entire process. By isolating the proving process for each block, the protocol can initiate proving tasks without waiting for a complete batch to be formed. This allows blocks to be processed in parallel as soon as they are generated, maximizing the utilization of prover resources and significantly improving overall proving efficiency.

- Timing in Stage 2 for Simplified Complexity: Compared to the first stage, the task of aggregating multiple block proofs into a single batch proof is far less computationally intensive and much faster. Therefore, the protocol chooses to initiate the aggregation stage only after all blocks within a batch have been proven, rather than adopting a more complex incremental aggregation approach. This design effectively reduces the management complexity of the

CodeControlGroup, as the context for the aggregation operation is a well-defined, completed batch. - Separation of Duties in Stage 3 for Integrity: Batch recursion is the key to ensuring integrity and achieving recursive compression. Separating it from the aggregation process is intended to create a clear division of responsibilities. The aggregation stage focuses on "intra-batch" state continuity, while the recursion stage handles "inter-batch" linking, connecting the validity of the current batch to the entire history of the chain. Its proving task is also more advanced and does not need to be executed concurrently with aggregation.

In summary, the entire system employs a pipelined execution of proofs not only within a single batch but also constitutes a higher-level pipeline across multiple batches. This nested pipeline design ensures high efficiency while keeping the verification logic of the CodeControlGroup within manageable limits, thereby guaranteeing the system's security and the convenience of upgrades.

4.2.3. Stage 1: Single Block Proving

The objective of this stage is to generate a validity proof for the execution of a single block. The process involves two steps:

- Off-Chain Simulation: Before proof generation begins, the system first simulates the execution of the block outside the zkVM. This step aims to acquire all necessary input data for the proof, including the read-write sets and their corresponding Merkle proofs.

- Stateless Proof Generation: The input data obtained from the previous step is provided to a stateless zkVM instance. The zkVM re-executes the state transition in a closed environment and generates a zero-knowledge proof.

The output of this stage is a Single Block Proof, which asserts the correctness of the block's execution. Its core content encapsulates the state roots before and after the block's execution (FromState and ToState), the unique block identifier (BlockNumber), and the commitment to the program used to generate this proof (CodeCommitment).

4.2.4. Stage 2: Batch Aggregation

This stage aims to aggregate the Single Block Proof from multiple consecutive blocks within a batch into a single proof. It performs two core functions:

- Verifying State Continuity: It checks and ensures that the state transitions between adjacent block proofs are continuous. That is, the

ToStateof block must be identical to theFromStateof block . - Recording Program Commitments: It extracts the

CodeCommitmentfrom each input proof and records it. A key feature of this stage is that it only records the commitments; verification against theCodeControlGroupis deferred to the next stage.

The output of this stage is a Batch Aggregated Proof, which represents the correctness of the entire batch's execution. This proof encapsulates the overall state transition of the batch, including the block height range of the batch (starting BlockNumber and ending BlockNumber), the initial state root of the first block in the batch (FromState), the final state root of the last block (ToState), and a complete list of the program commitments (CodeCommitment) recorded from all proofs within the batch.

4.2.5. Stage 3: Batch Recursion��

This is the core recursive step of the pipeline, designed to compress the ever-growing chain of proofs into a proof of constant size. The inputs for this stage consist of two parts:

- The Batch Aggregated Proof of the current batch (from Stage 2).

- The Batch Recursive Proof from the previous batch (from the previous run of Stage 3). For the system's first batch, this input does not exist; instead, the initial state root (

FromState) of its aggregated proof is checked directly against the protocol'sGenesisStateto anchor the beginning of the entire proof chain.

The core task performed by the zkVM in this stage is to comprehensively verify the authorization history of all executed program versions against the CodeControlGroup. This verification is based on the specific context (BlockNumber) in which each program was executed, as reflected in the following checks:

- Verifying Block Execution Programs: For each Single Block Proof in the batch, its

CodeCommitmentis verified against theCodeControlGroupusing its correspondingBlockNumberas theIndex. - Verifying Aggregation Program: The

CodeCommitmentof the current aggregation logic (Stage 2) is verified against theCodeControlGroupto its execution context. - Verifying Recursion Program: The

CodeCommitmentof the program used for the previous recursive proof is also verified against theCodeControlGroupusing its corresponding historical context.

In this way, the chain of trust is correctly propagated from the GenesisState through each recursion. The output of this stage is a new, updated Recursive Proof that encapsulates the history of all processed batches to date.

4.2.6. Stage 4: Proof Wrapping

This stage is the endpoint of the pipeline of the batch proving, with the core objective of converting the recursion proof from the previous stage into a highly optimized wrapped proof suitable for final verification on the Bitcoin network.

It takes the latest recursive proof and "wraps" it into a wrapped Groth16 proof. The Groth16 proving system is chosen for its ability to generate proofs of extremely small size and support exceptionally fast verification, which is crucial for achieving efficient verification under the computational and cost constraints of Bitcoin Script.

During the generation of this wrapped proof, the program version of the input recursive proof is verified against the CodeControlGroup. The complete CodeControlGroup is also compressed into its Merkle root, the CodeControlRoot, which is included as a public input in the wrapped proof. As the top-level program in the trust hierarchy, the wrapping program itself is not contained within the CodeControlGroup; its integrity is instead guaranteed by having its CodeCommitment directly hard-coded into the on-chain verification script.

4.3. On-Chain Verification via Bitcoin Script

The on-chain verification script template serves as the final arbiter of trust. As a result of the governance and pre-signing process synchronized with the Epoch lifecycle (as described in Section 4.4.1.1), a set of immutable trust anchors are hard-coded into the script for each Epoch. These anchors include:

- The

GenesisState, which anchors the starting point of the state. - The

CodeControlRoot, which commits to the entire authorization history of all upgradable programs for that Epoch. - The

CodeCommitmentof the non-upgradable wrapping program (Stage 4), which serves as the ultimate verifier.

During verification, the wrapped proof itself and its public inputs (including FromState, ToState, and CodeControlRoot) are provided as dynamic data. The core logic of the on-chain script is to check whether the CodeControlRoot provided as a public input in the proof exactly matches the CodeControlRoot hard-coded in the script for that Epoch. Based on this, the script combines these dynamic inputs with the static anchors to form a comprehensive ClaimHash. Subsequently, the BitVM protocol optimistically invokes the ZK proof verification logic. If the verification succeeds, it confirms the following facts:

- The state transition from

FromStatetoToStateis computationally valid according to the rules enforced by the zkVM programs. - All programs within the recursive proof were authorized by the

CodeControlRoot. - The wrapped proof was generated by the authorized wrapping program.

- The entire computational history can be traced back to the

GenesisState.

5. Bridging Bitcoin and Bitlayer Network

A secure rollup requires a correspondingly secure mechanism for asset transfers between the L1 and L2. This chapter details the Bitlayer Asset Bridge, the mechanism for transferring assets between Bitcoin and the Bitlayer Network. The bridge is built upon the same BitVM paradigm as our settlement protocol, ensuring a unified security model for both state validity and asset custody.

5.1. Roles

The bridge protocol involves several key roles:

- Users: Asset holders who initiate transfers between Bitcoin and Bitlayer Network.

- Broker: Assists users in preparing deposits and withdrawals, including constructing initial transaction graphs and obtaining signatures from Attesters. Brokers directly interface with users, abstracting the complexity of the BitVM protocol and enabling seamless interaction.

- Attesting Committee: This is the same validator set from the rollup protocol. The committee elected for a specific Epoch N is responsible for pre-signing the transaction graphs for all bridge requests initiated within that epoch.

- Watcher: Permissionless observers who monitor the protocol and challenge malicious behavior.

5.2. Asset Cross-Chain Flow

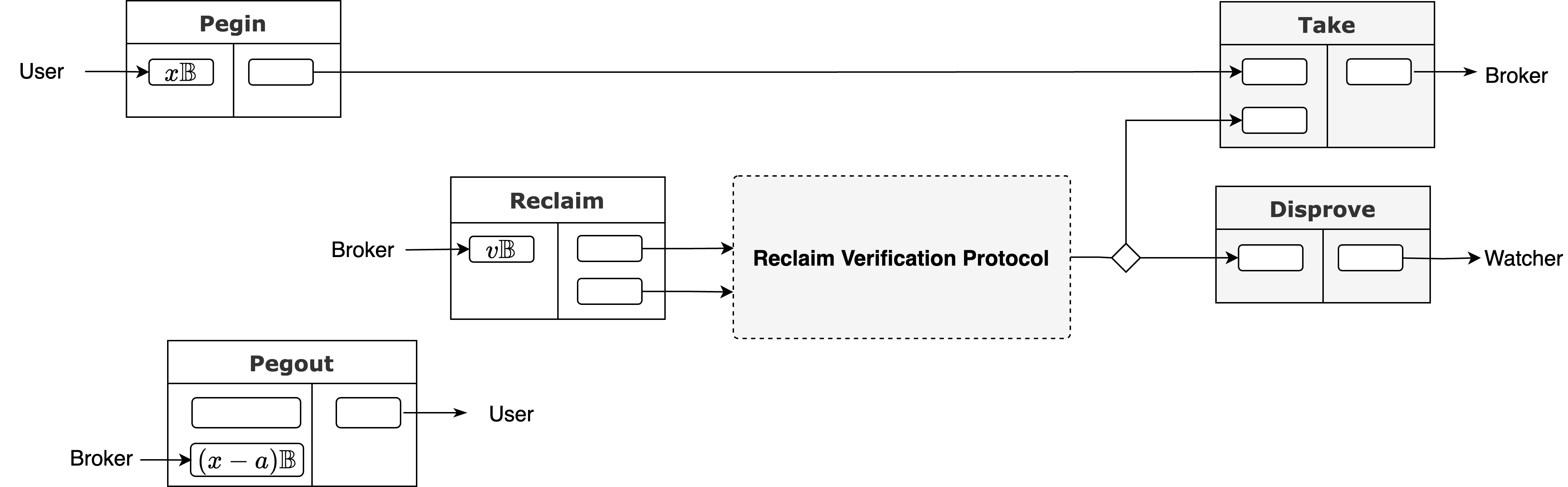

Below we use BTC as an example to introduce the complete process of asset deposit and withdrawal.

5.2.1. Asset Deposit (Peg-in)

The peg-in process moves assets from Bitcoin to Bitlayer and is initiated by the user in several steps:

- Initiate Request: The user submits a PeginRequest to all brokers, specifying the UTXOs for deposit, the target Bitlayer Network address, and a Bitcoin address for transaction change.

- Preparation: Each broker responds with a complete Pegin transaction and the associated transaction graph. The user must carefully verify all received transaction graphs for correctness, ensuring their parameters meet all expectations.

- Broadcast & Mint: After verification, the user issues the Pegin transaction on the Bitcoin network. Once the Pegin transaction is confirmed on L1, it is detected by the Bitcoin Light Client on the Bitlayer Network (as described in Chapter 4), which in turn triggers the Bitlayer protocol to automatically generate an intrinsic transaction. This transaction then calls the Bridge contract to mint the equivalent amount of BTC to the user's specified address.

5.2.2. Asset Withdrawal (Peg-out)

The standard peg-out process is designed for efficiency, relying on Brokers to provide upfront liquidity for a fast user experience:

- Initiate Burn: The user initiates a Burn transaction to the Bridge contract on the Bitlayer Network. This transaction burns a specific amount of BTC on the L2 and, crucially, includes a Partially Signed Bitcoin Transaction (PSBT) which defines the intended L1 withdrawal. The difference between the amount burned on L2 and the amount specified in the PSBT's output constitutes the fee for the Broker.

- Broker Fronts Funds: Brokers monitor the Bridge contract for these Burn transactions. A Broker who accepts the implied fee can fulfill the request by taking the user's provided PSBT, adding their own inputs and signature to complete it, and issuing the final transaction on the Bitcoin network. This mechanism ensures that only one Broker's front transaction can be successfully confirmed on-chain.

After fronting the funds, the Broker needs to reclaim their capital from the protocol through the security mechanism detailed below.

5.3. Broker Funds Reclamation

To recover their fronted funds, the Broker initiates a verification process by submitting a KickOff transaction to the protocol. This submission serves as an assertion that the Broker has legitimately fulfilled a valid Burn transaction. The verification follows the same optimistic, challenge-response game used for state settlement in Chapter 3, where the Broker's assertion is assumed correct unless challenged.

- Challenge Process: Watchers verify the legitimacy of this Reclaim Claim. If any invalidity is found (e.g., the corresponding

Burntransaction does not exist or is invalid), a Watcher will publish aChallengetransaction. - Assertion and Penalty: Upon being challenged, the Broker must respond within a specified time with an Assert transaction, which must contain a Groth16 ZKP. If a Watcher can verify that this proof is invalid, they can publish a Disprove transaction to penalize the Broker and receive a portion of their bonded collateral as a reward. This game-theoretic process is mechanically identical to the Single Claim Verification Protocol described in Chapter 3.

This reclaim verification mechanism relies on the Bitlayer Light Client and depends on the Bitcoin mainnet for the finality of Bitlayer Network transactions. Therefore, a Burn transaction is considered valid only after it has been included in a Batch and achieved Hard Finality on Bitcoin. If challenged, the Groth16 proof provided by the Broker must contain a complete verification chain from the Bitlayer Network's Genesis State to the current state to prove the validity and authenticity of the Burn transaction.

5.4. Escape Hatch

The bridge includes an escape hatch to guarantee user sovereignty over their assets, even if the L2 protocol halts. A halt can occur if the Operator repeatedly fails to submit new claims or if a submitted claim is successfully challenged. In this scenario, while the Operator's collateral is slashed and the L2 state is protected from further invalid updates, user funds could become locked. The escape hatch provides a new path for withdrawal, which also relies on Brokers for liquidity.

The process unfolds as follows:

- User-Initiated Forced Withdrawal: A user initiates an emergency withdrawal by broadcasting a force-inclusion withdrawal transaction directly to the Bitcoin L1. This transaction contains a signature proving ownership of the L2 account and specifies the L1 address for receiving the funds. While this L1 transaction cannot be fully processed by the stalled rollup, it serves as an immutable, on-chain withdrawal request.

- Broker Fronts Funds: Brokers monitor the Bitcoin L1 for these forced withdrawal requests. After aggregating a sufficient number of requests to meet a predefined threshold, a Broker can choose to front the liquidity, sending the funds directly to the users' specified L1 addresses.

- Broker Funds Reclamation: To reclaim their fronted capital, the Broker submits a reclaim claim to the bridge protocol, accompanied by a single Groth16 proof. This proof must validate three distinct conditions:

- Proof of L2 Halt: Evidence that the rollup protocol is stalled. This is confirmed either by showing a CommitBatchTimeout transaction (indicating the Operator's failure to submit a new batch) or a successful slash transaction (indicating the last submitted batch was fraudulent).

- Proof of Valid User Request: Evidence that the user's withdrawal request is legitimate. This requires proving the existence of the force-inclusion transaction on L1 (via the Bitcoin Light Client) and confirming the user had a sufficient balance in the last correctly finalized L2 state.

- Proof of Fulfillment: Evidence that the Broker has already sent the corresponding funds to the user on L1, also confirmed via the Bitcoin Light Client.

This escape hatch mechanism ensures that users always retain control of their assets, relying only on the security of the Bitcoin L1 and the economic incentives of the Broker network. We will explore using account abstraction to define more intelligent withdrawal logic and extending this mechanism to support the emergency withdrawal of assets held within smart contracts.

6. Security Analysis

This chapter presents a comprehensive analysis of the security that underpins the Bitlayer Rollup. We begin by introducing a general security model for BitVM-style smart contracts, followed by definitions and proofs of their safety and liveness properties. We then conduct a detailed analysis of the Bitcoin settlement security properties discussed in Chapter 3. Finally, we briefly described the inherent censorship resistance provided by decentralized networks.

6.1. BitVM-Style Smart Contract Security

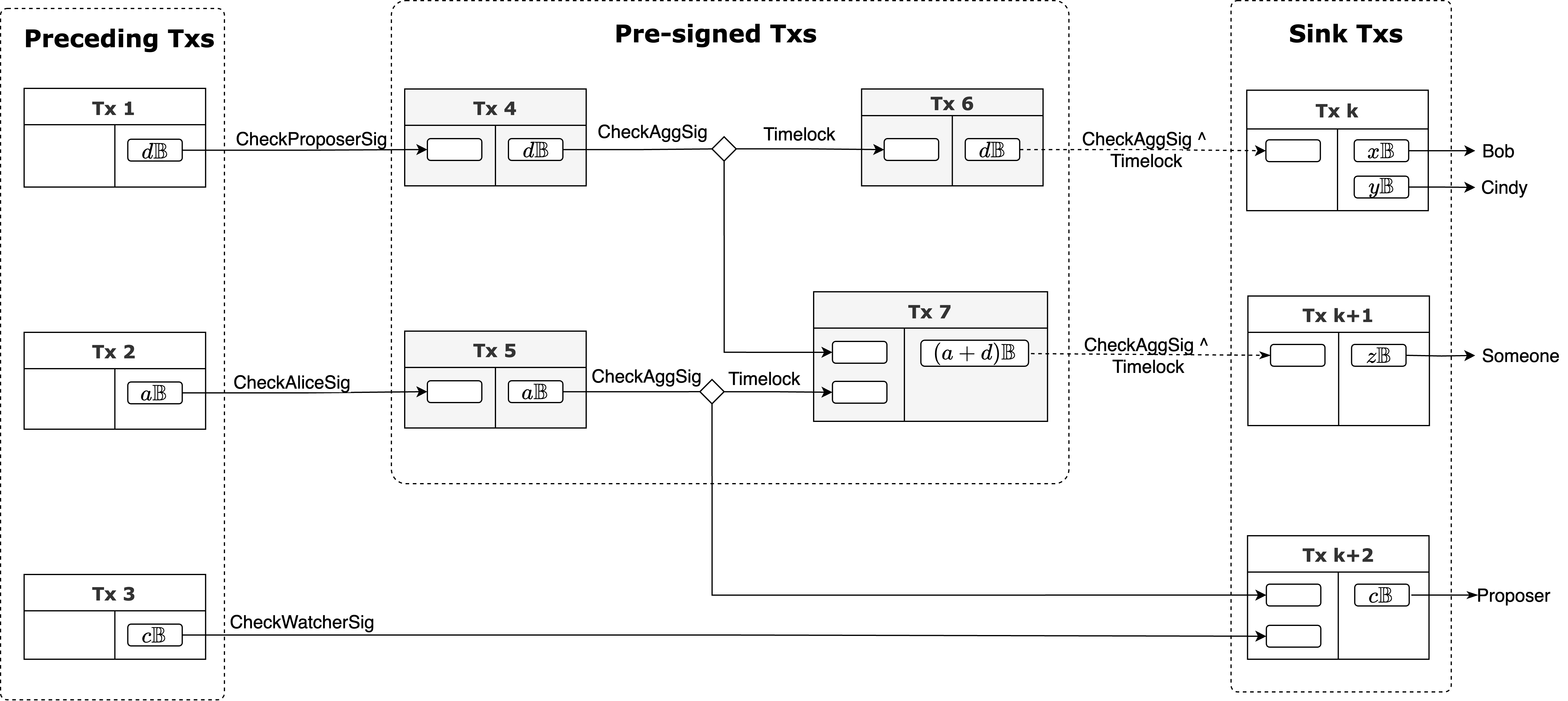

BitVM-style smart contracts follow a universal transaction graph structure. In this section, we provide a general security analysis applicable to all BitVM-style contracts, including the Bitlayer settlement protocol.

6.1.1. System Model & Assumptions

In a BitVM-style smart contract, at least three roles are required to collaborate:

- Transaction Graph Proposer: The Proposer is responsible for initiating a contract instance. To do so, the Proposer must stake a predefined amount of BTC, serving as both a commitment and collateral against misbehavior.

- Attesters: We assume there are Attesters, among whom are honest. The remaining are semi-honest, meaning that they follow the protocol and collaborate to construct the pre-signed signature but may behave unpredictably off-protocol, such as retaining keys after pre-signing, which may allow them to attempt signing additional unauthorized transactions after the pre-signing is completed. Each pre-signing requires the participation of at least Attesters.

- Watchers: Watchers monitor the on-chain state submitted by the Proposer to ensure correctness. If misbehavior is detected, they can issue a Challenge transaction to hold the Proposer accountable by invoking penalties on the staked BTC. The model assumes the existence of at least one rational, honest, and active Watcher.

Additionally, we assume a synchronized network, where all communications between participants and the Bitcoin network occur within a known bounded time . All participants are assumed to be rational and polynomial-time bounded, meaning all cryptographic tools used in the BitVM-style smart contract are secure.

6.1.2. Transaction Graph Model

The transaction graph serves as the backbone of the BitVM-style smart contract, structured as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). This model provides clarity and enforceability to the contract’s execution.

- Preceding Transactions: The transactions provide the initial outputs necessary for the contract’s execution, which include the Proposer’s stake reserve and the Watcher’s reserve. The Attesters must validate the existence and correctness of these transactions before pre-signing.

- Pre-signed Transactions: The transactions that Attesters need to pre-sign, which determines the logic of the BitVM-style contract.

- Sink Transactions: The transactions, lacking outgoing edges in the DAG, signify the release of funds.

6.1.3. Design Principles

- Stake: The Proposer must stake a specified amount of BTC to initiate the contract. ( BTC in the graph).

- Slashable: Incorrect STF submitted by the Proposer can result in the slashing of their staked BTC.

- Termination: All outputs containing amounts in the pre-signed transactions must have a time lock path (which may involve multiple transactions) leading to Sink transactions, ensuring the contract eventually terminates.

6.1.4. Safety

Safety Goals

- Validity: Every transaction in the transaction graph must be valid after pre-signing.

- Integrity: No new transactions can be added to the transaction graph after pre-signing.

- Flexibility: The BitVM-style smart contract can accommodate different security assumptions, depending on the application scenario.

Lemma 1 Let be the pre-signed transactions spending . No transaction can spend .

Proof: We prove this important lemma by contradiction. Assume a committee performed the pre-signing. If exists, it indicates that the Attesters have performed additional signing outside of the pre-signing process, which implies that these Attesters are semi-honest. This contradicts the assumption.

Lemma 2 Each pre-sign committee must include at least one honest Attester.

Theorem 1 (Validity): If a valid pre-signed signature is produced for a transaction , then is valid.

Proof: By Lemma 2, at least one honest Attester participated in the pre-signing and contributed partial signature for . Hence, received by must be valid. Since the validity of relies on all Attesters contributing partial signatures to , it must be valid.

Theorem 2 (Integrity):

Proof: Except for Sink transactions, all outputs must require a multi-signature from the pre-sign committee. By Lemma 1, we can conclude that all participants can only spend the UTXOs in the transaction graph along the predefined path, ensuring the integrity of the BitVM-style smart contract.

Theorem 3 (Flexibility):

Proof: We can dynamically adjust the security assumptions of the Attesters based on the requirements of the application scenario, as long as the pre-sign committee ultimately includes at least one honest node. Based on Lemma 1 and Lemma 2, validity and integrity can then be deduced.

6.1.5 Liveness

Liveness Goal

- Funds Liquidity: Funds involved in the contract’s Preceding transactions must not remain indefinitely locked.

Theorem 4 (Funds Liquidity):

Proof: Since the time lock duration is known and finite, the Termination principle of the transaction graph ensures that all funds will eventually be unlocked and flow to Sink transactions within a finite time.

6.2 Bitcoin Settlement Security

This section focuses on proving the Bitcoin settlement security properties introduced in Chapter 3.4.4.

Theorem 5 (Completeness): An honest Operator who correctly follows the protocol and submits valid state claims will never be unjustly penalized.

Proof: An honest operator publishes valid claims and sub-program results within the required time windows, ensuring no inconsistencies arise. As a result, no watcher can unlock a Disprove Script, and the operator is not penalized. To save space, the details are omitted here.

Theorem 6 (Soundness): A dishonest Operator who submits a fraudulent claim cannot avoid being penalized, as an honest Watcher will always be able to construct a valid Disprove transaction.

Proof: If the dishonest operator does not publish within , the operator will be penalized. During the Claim Phase, the dishonest operator publishes . will fail locally for watchers, they raise a challenge within , moving the protocol to the Challenge Phase. If the operator does not publish the result of all sub-programs within time , the operator will be penalized.

If there is a disproved algorithm allowing watchers to unlock a Disprove Script with inputs and outputs published by the operator that contradict the sub-program execution, then a dishonest operator cannot escape penalties.

We prove the existence of the disprove algorithm as follows. First, since the inputs and outputs published by the operator contradict the local sub-program execution, there must be at least one inconsistent output produced by the sub-program, saying . Then, we check the consistency of the inputs of . If all inputs are consistent, we select as the challenged sub-program, otherwise recursively run the first step for one of the inconsistent inputs. So, the disprove algorithm must successfully select a sub-program to challenge.

Theorem 7 (Efficiency): The entire claim verification process, whether it results in acceptance or rejection, is guaranteed to terminate within a bounded timeframe defined by the protocol's time locks.

Proof: Each phase of the protocol has a bounded time. If both the Operator and Watcher are honest in following the protocol, the optimistic time bound is . If either the Operator or any Watcher tries to destroy the protocol, the time-bound will become . Thus, the maximum time bound to confirm is , so that the protocol terminates regardless of whether the claim is accepted or rejected. Thus, the protocol guarantees efficiency by design.

6.3 Censorship Resistance

Unlike traditional L2 architectures that rely on a single sequencer, our design employs a rotating manner among validators to produce blocks. This decentralized sequencing mechanism ensures that no single party can unilaterally censor transactions. As block production rotates among validators in a permissionless and stake-weighted manner, any attempt to exclude valid transactions can be bypassed in subsequent blocks, providing strong built-in censorship resistance and enhancing the neutrality of the network.

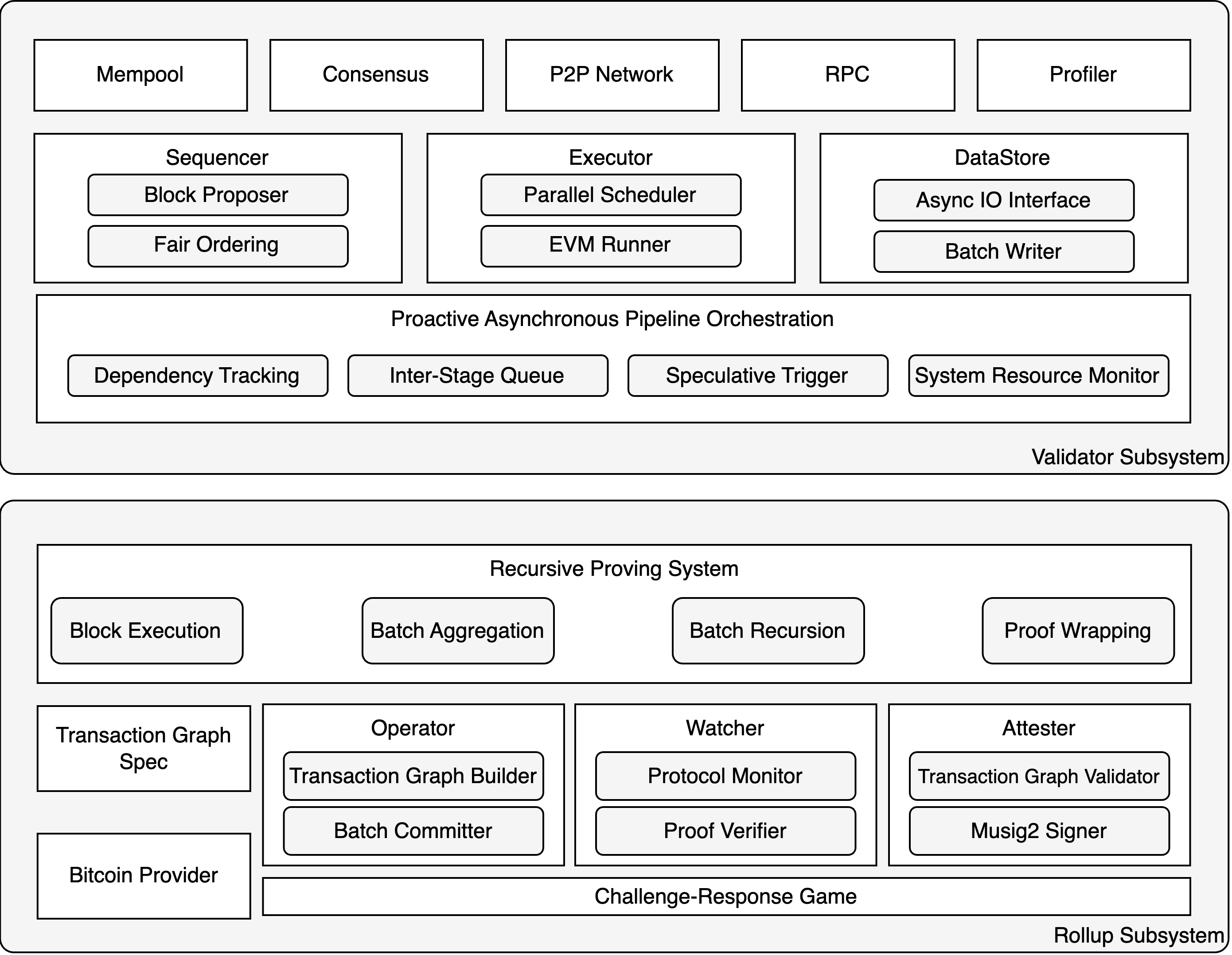

7. System Architecture

A robust and well-engineered system architecture is paramount to achieving Bitlayer's dual goals of high performance and trust-minimized security. At the heart of our design is a dual-subsystem model that cleanly decouples the L2's high-throughput execution layer from its L1 settlement and security layer. This chapter details this architecture, starting with the core principle of decoupling, followed by a system-level overview of the data flow, and a detailed analysis of the components within both the Validator (Performance) Subsystem and the Rollup (Security) Subsystem.

7.1 Decoupling of L2 Execution and L1 Settlement

The core design principle of the Bitlayer architecture is the decoupling of L2 execution from L1 settlement. This strategic partition divides the system's functionalities into two distinct domains: a Validator (Performance) Subsystem and a Rollup (Security) Subsystem.

- The Validator Subsystem: This subsystem is a high-performance blockchain focused exclusively on processing L2 transactions (including L1 Forced Transactions), including transaction ordering, smart contract execution, and state storage. It is designed for high throughput and low latency to provide users with sub-second soft finality. Its performance depends only on its own consensus and computation technologies, independent of L1 interaction. We therefore refer to this subsystem as the Performance Domain, as it is built for high-frequency state computation.

- The Rollup Subsystem: This subsystem anchors the state and security of the Validator Subsystem to the Bitcoin network. It is responsible for all L1 interactions, including state commitments and the fraud-proof challenge-response protocol. Its security guarantees are cryptographically traceable to Bitcoin's Proof-of-Work consensus. We therefore refer to this subsystem as the Security Domain, as its purpose is to ensure the integrity of the L1 settlement process.

Similar to a microservices architecture, this separation of concerns allows each subsystem to be developed and optimized independently. For example, optimizations to the Validator Subsystem, such as upgrading the consensus engine, can proceed without altering the L1 interaction protocol. Conversely, the Rollup Subsystem can integrate new proving systems without re-architecting the core L2 execution layer. This modular design ensures the system is both robust and adaptable to future technological changes.

7.2 The Validator Subsystem

The Validator Subsystem is engineered exclusively for performance. Its architecture is composed of three core components: a Decentralized Sequencer, a Parallel Execution Engine, and a High-Concurrency Data Store. These components are integrated via a proactive computation pipeline, which collectively constitutes the primary driver of Bitlayer's transaction throughput and low-latency characteristics, providing the capacity to support peak loads in the order of tens of thousands of transactions per second (TPS).

7.2.1 Decentralized Sequencer

The sequencer functions as the ordering and consensus core of the Bitlayer platform. It is implemented as a decentralized network of validators operating under a Proof-of-Stake (PoS) protocol. Its primary design objective is to furnish a trustless, credibly neutral mechanism for transaction ordering, thereby mitigating the risks inherent in centralized sequencers, such as single points of failure, malicious transaction reordering (e.g., MEV extraction), and censorship. The sequencer network receives transactions from across the network and utilizes a high-performance BFT consensus protocol to establish a canonical, global ordering for these transactions within a block, which then attains economic-stake-backed soft finality.

7.2.2 Parallel Execution Engine

The execution engine is designed to overcome the performance limitations of the EVM's sequential execution model. The principal challenge in parallelizing EVM execution is its interleaved state access pattern, which complicates dependency prediction. Our core innovation is a dependency analysis and state conflict resolution mechanism specifically optimized for this environment. It leverages principles from Optimistic Concurrency Control, adapted for the blockchain context. The engine speculatively executes transactions in parallel under the assumption of non-conflict, with coordination mechanisms engaged only upon detection of a data dependency. Advanced techniques, including operation-level conflict resolution and hint-based proactive scheduling, are employed. This enables the engine to re-execute only the minimal set of conflicting operations, rather than entire transactions, thereby maximizing the utilization of multi-core processor architectures and significantly elevating the transaction processing capacity.

7.2.3 Blockchain-Native Storage Engine

The data store is a high-performance persistence layer tailored to the access patterns of the parallel execution engine. It addresses the bottlenecks of general-purpose databases (e.g., LevelDB/RocksDB), such as state bloat and I/O contention. It is responsible for storing all canonical blockchain data, including the account state, smart contract code, and transaction receipts. Performance is achieved through asynchronous I/O interfaces and batched writes, which decouple execution from storage latency. Architecturally, it employs index and key-value (KV) separation and semantics-aware data partitioning. This design minimizes lock contention and reduces write amplification, providing robust storage support for the high-concurrency demands of the parallel execution engine.

7.2.4 The Proactive Computation Pipeline

The Validator Subsystem integrates its components into an asynchronous, multi-stage pipeline that implements a principle of proactive computation, analogous to out-of-order execution in modern CPUs. Instead of a rigid, sequential paradigm (Consensus -> Execute -> Persist -> Checkpointing), our pipeline deconstructs these tasks to enable temporal overlapping. This allows the system to work on multiple blocks simultaneously at different stages; for example, the consensus process for ordering transactions in Block N+1 can run concurrently with the execution of Block N. This overlapping of consensus and execution is key to maximizing resource utilization and significantly reducing end-to-end transaction latency.

7.3 The Rollup Subsystem

This section details the components that verifiably settle the computational results of the Validator Subsystem on the Bitcoin network, endowing the Bitcoin blockchain with the capability for active state verification and dispute resolution.

7.3.1 Recursive Proving System

The cryptographic foundation of Bitlayer's security is its Recursive Proving System. This system, implemented as an asynchronous Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) generator, is tasked with producing a single, succinct, and irrefutable proof of validity for all state transitions within a settlement period. A key design innovation is its complete decoupling from the L2's critical performance path. Proof generation operates as a background process, ensuring that L2 block production rates and transaction confirmation latencies are independent of the computationally intensive proving process. This architecture facilitates the future development of a permissionless Proving Market to further optimize proving efficiency and cost through market-based competition.

7.3.2 Engineering Implementation of the L1 Finality Protocol

The translation of the complex BitVM-based protocol into an automated and robust system represents a core engineering challenge addressed by the Rollup Subsystem. A modular software design maps protocol roles to specific components, ensuring system maintainability, security, and extensibility. The implementation is centered around three primary software entities: the Operator, the Watcher, and the Attester.

- Operator: The Operator is the primary agent responsible for advancing the protocol. It is an automated software suite comprising several internal modules:

Transaction Graph Builder: This module is the core implementation of the BitVM paradigm. It deterministically constructs a complex Bitcoin transaction graph from L2 state batches, in strict adherence to theTransaction Graph Specification. This involves programmatically generating Bitcoin Scripts for all challenge-response pathways and embedding the L2 state root via hash locks.Batch Committer: This module optimizes L1 interaction costs by aggregating state commitments from multiple L2 batches into a single ClaimTransaction, thereby amortizing the on-chain footprint.Challenge Responder: This defensive module monitors the L1 for challenges against its commitments. Upon detection, it retrieves the corresponding ZK proof from the Proving System and broadcasts the appropriate response transaction as defined in the specification.

- Watcher: Representing the decentralized security mechanism, the Watcher is software that can be run by any full-node participant to audit the Operator.

Proof Verifier: This module independently fetches state commitments from L1 and corresponding L2 block data. It re-executes the state transitions to verify the integrity of the Operator's submitted state root, serving as the first line of defense against fraud.Challenger: If theProof Verifierdetects a discrepancy, theChallengermodule is activated to construct and broadcast a challenge transaction on L1, thereby initiating the on-chain dispute resolution process and contesting the Operator's staked collateral.

- Attester: A set of highly-staked validators provide security for the validity of the transaction graph.

Transaction Graph Validator: Prior to signing, each Attester utilizes this module to independently validate the Operator-constructed transaction graph against the formal specification, ensuring it contains no exploitable or invalid paths.Musig Signer: Upon successful validation, this module employs an advanced multi-signature scheme (e.g., MuSig2) to produce a single, aggregated signature for the transaction graph. This engineering choice provides superior efficiency, privacy, and scalability over traditionalCHECKMULTISIGoperations.

These components interface with the L1 via a Bitcoin Provider module (an RPC wrapper), forming an automated L1 finality system with a clear separation of duties. This modular implementation enhances testability and maintainability while providing a solid foundation for future protocol upgrades.

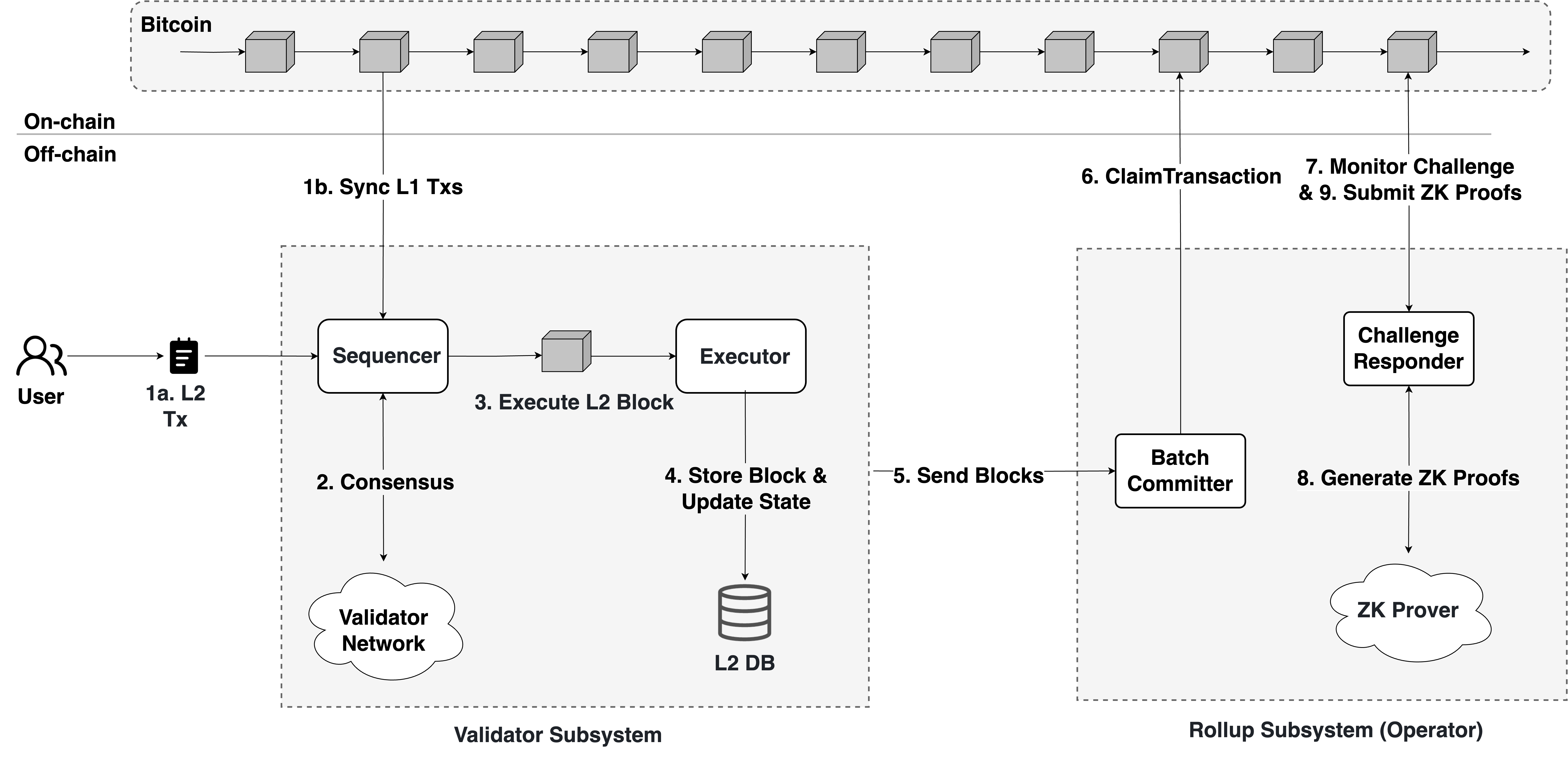

7.4 Transaction Lifecycle

- Sequencing: Users initiate transactions on the L2 network (Step 1a). These transactions are collected by the Sequencer component within the validator, while on-chain interactions (Step 1b), such as deposits and force inclusion transactions, are submitted to Bitcoin. The Bitcoin Listener component continuously monitors the Bitcoin network and synchronizes L1 transactions to the Sequencer.

- Block Consensus: After collecting the transactions, one of the Sequencers is selected to propose a set of transactions. All validators then reach an agreement on the ordering and content of the proposal through the consensus (Step 2). Once consensus is achieved, a sequenced L2 block is produced (Step 3).

- Execution: Once a block is produced, it is immediately executed by the validator. The Executor performs parallel execution of the block's transactions to compute the new world state.

- Persistency: The new state is efficiently persisted. At this point, the L2 block achieves soft finality (Step 4).

- Inter-Subsystem Handoff: Upon reaching soft finality within the validator network, the state data of an L2 block is transmitted to the Rollup Subsystem via the internal asynchronous API. This asynchronous communication is critical for performance isolation, ensuring that the high throughput of the Validator Subsystem remains unencumbered by the proof-generation latency of the Rollup Subsystem (Step 5).

- State Claim: The Operator's Batch Committer component aggregates multiple block data, assembles rollup batch information, and starts the Bitcoin settlement process as described in Chapter 3 (Step 6).

- Challenge Responder: When a Watcher challenges the state claim posted by the Operator on Bitcoin (Step 7), the Operator responds by generating a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) to defend the correctness of the claimed state (Step 8). The Prover generates a ZKP based on the execution trace and state transition, which is then submitted by the Operator to Bitcoin (Step 9) as evidence supporting the validity of the rollup state.

7.5 Conclusion

Ultimately, the Bitlayer V2 architecture establishes a clear blueprint for scaling Bitcoin: it leverages Bitcoin as the ultimate decentralized trust and settlement layer, while Bitlayer Network functions as a high-throughput, verifiable computation layer built atop it. This design provides a viable pathway to unlock the vast, dormant capital in the Bitcoin ecosystem, laying a foundational infrastructure for a secure, scalable, and vibrant decentralized finance ecosystem on Bitcoin.

8. Limitations and Future Directions

This chapter reflects on the current design of the Bitlayer Network, discussing its inherent trade-offs and the promising research avenues they inspire. We first outline the primary limitations of our current protocol and then detail future work aimed at addressing these challenges and further advancing the capabilities of Bitcoin L2s.

8.1 Limitations

While the Bitlayer Network provides a robust framework for a Bitcoin computational layer, its current design involves several trade-offs:

- Dependency on Validator Set's Honesty: The security of the bridge and settlement protocol currently relies on an honest majority assumption within the active validator set, which serves as the Attesting Committee. While this security is cryptographically enforced, it represents a trust assumption beyond Bitcoin's own proof-of-work. Eliminating this reliance on an external honest-majority through future Bitcoin protocol upgrades remains a key goal for achieving a more fully trustless system.

- Centralized Operator and Liveness: The current model uses a single, rotating Rollup Operator for sequencing and settlement. While this is efficient, it presents a potential single point of failure for liveness if the operator goes offline. This motivates the development of a multi-operator mechanism.

- Reliance on Broker Liquidity: The fast withdrawal and emergency escape hatch mechanisms depend on an active network of third-party Brokers to provide upfront liquidity. The system's user experience and capital efficiency could be further improved by protocol-native solutions that reduce this reliance.

8.2 Future Directions

We are actively researching several enhancements to address these limitations and expand the network's capabilities:

- Leveraging Future Bitcoin Upgrades (Covenants): Upcoming potential Bitcoin protocol upgrades, such as those introducing new covenant opcodes (e.g.,

OP_CTV[10],OP_CAT, or similar proposals), could pave the way for more trustless smart contract functionalities directly on Bitcoin. We are closely monitoring these developments and plan to integrate such features, if and when they become available and stable. This could allow for:- Elimination of Attesting Committees: Potentially removing the need for an attesting committee for certain verification processes, moving towards a more fully trustless model.

- Enhanced Permissionlessness: Reducing reliance on pre-signed transactions or specific roles in the dispute resolution protocol, making the system even more open.

- On-Chain Operator Election: Managing Rollup Operator election and rotation more directly on-chain, further enhancing liveness and decentralization.

- Optimized Collateral Management: Enabling more sophisticated collateral reuse mechanisms within the same epoch without compromising security, thereby reducing the capital costs for operators.

- Advanced Proving Systems: Continuously evaluating and integrating advancements in zero-knowledge proof systems and other cryptographic techniques to improve proof generation efficiency, reduce on-chain verification costs, and enhance overall system performance.

9. Conclusions